Introduction

Needle sticks and sharp injuries (NSSIs) are a common occupational hazard in the healthcare sector, which includes dentistry practices. These accidents have the potential to have serious long-term effects as well as acute health issues, making them a danger to the safety of healthcare practitioners. Although NSSIs have received attention in the larger healthcare environment, careful examination of the particular intricacies within the dentistry profession is warranted. Essentially, 12% of workers worldwide are healthcare professionals (HCWs) (Akbari, Ghadami, Taheri, Khosravi, & Zamani, 2023). This population has several obstacles, most notably the increased risk of mucocutaneous contamination and bloodborne illnesses from NSSIs (Abalkhail, Kabir, & Elmosaad, 2022; Alsabaani, Alqahtani, & Alqahtani, 2022; Mohamud, Mohamed, & Doğan, 2023; Mubarak, Ghawrie, Ammar, Abuwardeh, & R, 2023). According to published figures, needle-stick injuries (NSIs) are responsible for over 40% of instances of Hepatitis B (HBV) and Hepatitis C (HCV), as well as 2.5% of cases of HIV/AIDS-related infections among healthcare workers worldwide. Additionally, it is estimated that over 90% of these occupational illnesses happen in low-resource healthcare settings where there is not enough compliance with current infection prevention standards (Alfulayw, St, & Alqahtani, 2021).

NSSIs nevertheless transpire at each phase of making use of and disposing of sharp objects, even though the World Health Organization (WHO) has issued standards for minimizing NSIs in medical facilities (Patsopoulou, Anyfantis, & Papathanasiou, 2022). According to statistics, approximately 32.4% and 44.5% of healthcare professionals worldwide endure at least one needle-stick or sharp injury every year. Based on current information, around 385,000 NSIs are reported annually among hospital healthcare personnel in the United States. At the same time, evidence indicates that yearly, up to 1,000,000 NSIs concerning hospital healthcare personnel occur throughout European countries. Accidental exposure continues to be a significant workplace danger despite great efforts and necessitating continued attention and better prevention measures (Bouya, Balouchi, & Rafiemanesh, 2020; Mengistu, Tolera, & Demmu, 2021).

Numerous factors affect the likelihood that healthcare workers might sustain injuries from needle sticks and other sharps encounters. These consist of safety precautions and the use of needles or other sharp items (Berhan, Malede, & Gizeyatu, 2021). The number of patients at a healthcare facility and precautions that staff members adopt while engaging with patients impact the hazards of these exposures. Medical professionals such as nurses, doctors, lab technicians, and medical waste handlers are more likely to acquire injuries from sharp objects (Letho, Yangdon, & Lhamo, 2021) when performing tasks including screening, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and medical waste disposal. All pertinent professions can benefit from reduced risk of unintentional needle-stick and other percutaneous injuries by the use of safety equipment and adherence to exposure prevention methods.

Bloodborne infections are made more likely by the dental environment, which the frequent use of sharp instruments, blood, saliva, and different microbes in the mouth cavity (Ravi, Shetty, & Singh, 2023) has defined. Dental practitioners' exposure to infectious illnesses, patient load, needle recapping practices, experience, and compliance with infection control protocols are all risk factors for NSSI (Al-Zoughool, Al-Shehri, & Z, 2018). Specific hazards related to dental operations and working circumstances have been discovered by regional studies, such as those conducted in Germany (Wicker, Jung, Allwinn, Gottschalk, & Rabenau, 2007) , Taiwan (Younai, Murphy, & Kotelchuck, 2001) , Mongolia (Kakizaki, Ikeda, & Ali, 2011) , China (Cui, Zhu, Zhang, Wang, & Li, 2018), and Kabul (Salehi & Garner, 2010).

It has been observed that third-year undergraduate students are more vulnerable since they lack expertise in executing invasive operations (Younai et al., 2001). To reduce the risk of sharps injuries among dental students, adequate education and training are essential (Cheetham, Ngo, Liira, & Liira, 2021). Despite these dangers, dental professionals continue to underreport NSSI incidents 20 like other healthcare professionals.

This study addresses the critical need to fully comprehend dental practitioners' knowledge, attitudes, and practices around NSSI. Despite a wealth of research on more general issues of bloodborne illness exposure among healthcare workers, the dental environment is still poorly studied. By offering particular insights on NSSI among dental professionals, guiding focused measures, and improving the general safety of healthcare workers, this study seeks to close this knowledge gap.

Material and methods

Ethics approval

The work has been carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). No personally identifiable data were collected, and responses were anonymous from the point of entry. The approval of the research ethics committee was obtained from the College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Indore, India, with the Ethics approval code (CDSH/738/2023). As the questionnaire was anonymous, informed consent was not applicable. The survey was anonymous and voluntary.

Sample size estimation

The sample size was computed by applying the information provided for the population frequency estimate. The calculation was based on a design effect (DEFF) of 1, suggesting a non-cluster survey design with a population size (N) of 1,000,000 and an estimated percentage frequency of the outcome factor (p) set at 70.87%, coupled with a 5% margin of error. As a result, it was calculated that a sample size of around 318 was required for a 95% confidence level. Considering a 5% margin of error, this sample size allows for calculating the outcome factor's prevalence in the population.

Study approach

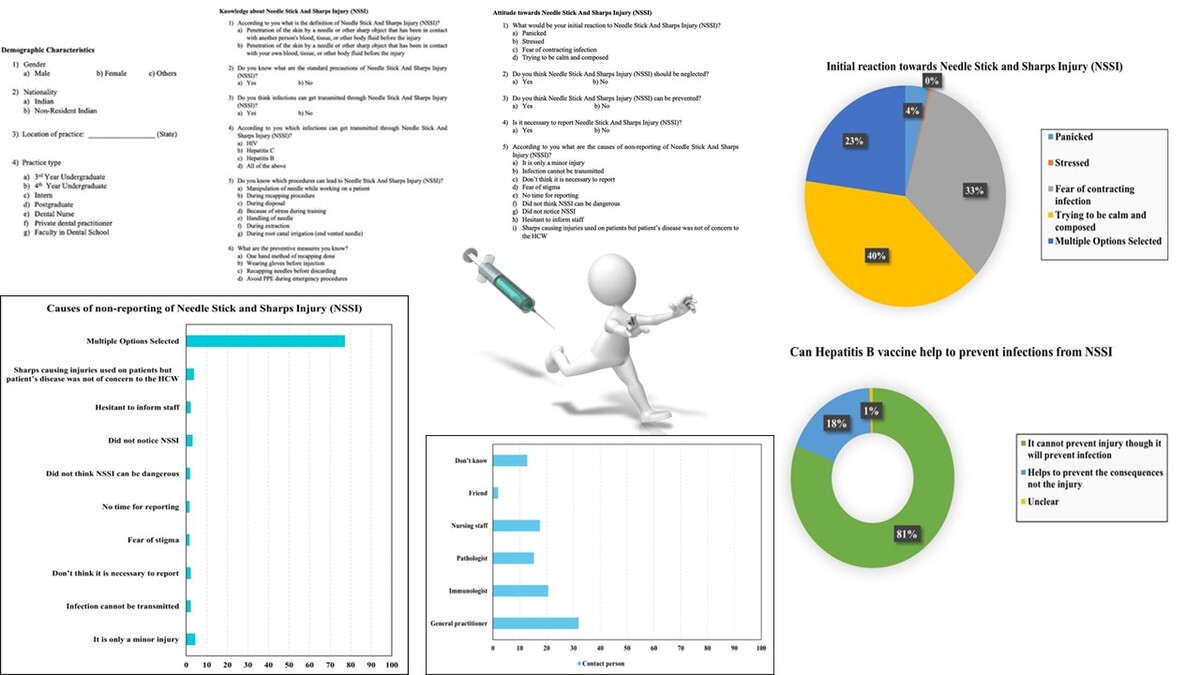

An organized, pretested, guided interview-based questionnaire with open-ended and closed-ended questions was used to gather information and details for the study. The pretest involved a pilot group of (Pervaiz, Gilbert, & Ali, 2018) healthcare professionals, whose feedback was used to refine the questions and improve clarity. This step ensured that the final questionnaire was well-suited to the target population. The 25-question survey included a section on demographic information, including age, gender, and the type of profession. The other part gathered information on knowledge (Figure 1) regarding NSSI, while the other two sections constituted the attitude (Figure 2) and awareness (Figure 3) about NSSI. The questionnaire offered several alternative responses to ascertain the healthcare workers' knowledge, attitude, and use of general precautions in the medical area, as well as their comprehension of NSSI.

The survey link was created using Google Forms and distributed to healthcare professionals via various professional and social networks, including emails and professional WhatsApp groups, to collect replies. Participants were only permitted to register once to prevent duplicate submissions, and the survey's title and aims were indicated on the main page. Each participant signed a permission form after receiving information about the study, and their names were kept confidential. The participants were third- and fourth-year undergraduate students, interns, post graduate students, dental school instructors, private dental practitioners, and dental nurses.

The Shinde Atram and Pawar (SAP) needle stick and sharps injury (NSSI) questionnaire was used in this investigation. Copyrighted and registered with the Copyright Office of India, this proprietary questionnaire bears registration number L-129836/2023, registered on July 14, 2023.

Statistical analysis

The data was inputted into Microsoft Office Excel, and the analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) Version 21. Frequency and Percentage were obtained for categorical data, and Chi Square Test of Proportion was applied to assess the difference in proportion between Variables. All the statistical analysis was done keeping the confidence interval at 95% (p<0.05) and was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

The demographic details and participants are presented in Table 1. There was a notable gender difference between the 320 participants, with 25.6% being men and 74.4% being women (P < 0.05). Merely 1.3% of participants were non-resident Indians, making up the majority of participants (98.8%) who were Indian nationals. The percentages of practice types varied, with the most prominent group being Private Dental Practitioners (35.3%), followed by Interns (28.8%) and Third Year Undergraduate Students (18.4%) (P < 0.05). Interestingly, 5.6% of participants misinterpreted NSSI as contact with their blood or tissue, whereas 94.4% of people correctly characterized it as skin penetration by a needle or sharp instrument that has come into touch with another person's blood or tissue.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics.

Table 2

Knowledge about Needle Stick and Sharps Injury (NSSI).

Knowledge about NSSI

The participants' knowledge of needle stick and sharps injuries (NSSI) and related preventative strategies is displayed in Table 2. Of the 320 individuals, 85.9% confirmed that they knew the basic precautions for NSSI, whereas 14.1% disagreed (P < 0.05). Interestingly, every participant understood that NSSI may potentially spread illnesses. Concerning the particular illnesses, 96.6% stated that NSSI may spread HIV, Hepatitis B, and other pathogens, but fewer respondents mentioned specific pathogens (P < 0.05). When asked which procedures result in NSSI, most respondents (85.6%) chose more than one, with the most often identified operation (6.3%) (P < 0.05) being the manipulation of needles during patient care. 72.8% of participants chose more than one preventative strategy, with the "one-hand method of recapping" being the most popular choice (11.6%) (P < 0.05).

Attitude towards NSSI

Of the 320 participants, 127 (39.7%) reported trying to maintain composure when asked about their opinions about NSSI and early reactions to NSSI. In addition, 107 individuals (33.4%) reported being afraid of becoming infected, while 73 participants (22.8%) chose multiple responses. The difference in proportions was determined to be statistically significant (p<0.05) even though just one participant (or 3%) said they felt stressed (Figure 4). NSSI should not be ignored, according to a significant majority of 306 participants (95.6%), with this difference in proportions also showing to be statistically significant (p<0.05). The belief that NSSI could be prevented was also shared by 317 individuals (99.1%), and this difference in proportions was statistically significant (p<0.05) (Figure 5).

Of the 320 participants, 247 (77.2%) gave numerous replies about the possible causes of NSSI non-reporting. Among these were the notion that the damage was insignificant (14 participants, or 4.4%), false beliefs regarding the spread of illnesses (7 participants, or 2.2%), and stigmatization fears (5 participants, or 1.6%). Additionally, statistically significant (p<0.05) was this discrepancy in the proportions (Figure 6).

Awareness about NSSI

A substantial majority of 293 people (91.6%) out of 320 participants said that thorough washing with soap and water is crucial for controlling NSSI. Participants showed no discernible variation in proportions when asked about their propensity to press the injury to cause bleeding (p>0.05). The difference in proportions between the two groups was statistically significant (p<0.05), with 303 individuals (94.7%) expressing the opinion that finger pricks shouldn't be put in the mouth. Only 269 individuals (84.1%) reported being aware of PEP (Post-Exposure Prophylaxis), and this difference in proportions was statistically significant (p<0.05) (Figure 7).

In response to the question of whom to contact regarding a needle stick or sharps injury (NSSI), 102 (31.9%) of the research participants said they would call a general practitioner. The difference in proportions between the two groups was statistically significant (p<0.05), with 41 individuals (12.8%) unsure about the proper contact (Figure 8). Two hundred fifty-seven individuals, or 80.3%, agreed that the Hepatitis B vaccination would help prevent NSSI; 59 participants, or 18.4%, disagreed; and 2 participants, or 0.6%, were undecided (Figure 9). The proportional difference was statistically significant (p<0.05) (Figure 6). Notably, just 1 participant (0.3%) thought the Hepatitis B vaccine was unnecessary, whereas 319 people (99.9%) thought it was required. This difference in proportions was statistically significant (p<0.05).

There was an extensive discrepancy in participants' knowledge of the Hepatitis C vaccination, with 254 individuals (79.4%) stating there is no Hepatitis C vaccine and 66 participants (20.6%) confirming its presence. The proportional difference was statistically significant (p<0.05).

A sizable portion of the 228 participants (71.3%) who were questioned about their sources of knowledge for preventing NSSI submitted various answers. This list of alternatives includes reading up-to-date journal articles (11 participants, or 3.4%), taking part in various training courses (13 participants, or 4.1%), going to a variety of continuing medical education (CME) seminars (32 participants, or 11.3%), and reviewing Centre for Disease Control (CDC) recommendations (36 participants, or 11.3%). The proportional difference was statistically significant (p<0.05) (Figure 10).

Discussion

For healthcare workers, NSSI accidents represent severe work-related dangers. Even though medical institutions are advised by the World Health Organization (WHO) to minimize these injuries, these incidences happen on various levels. Remarkably, out of 320 respondents, 94.4% showed that they understood the notion of injuries from needle sticks and sharp objects (Saadeh et al., 2020). Furthermore, 86% of participants showed that they understood the standard safety measures meant to avoid needle-stick injuries and to keep themselves away from sharp items (Berhan et al., 2021).

Dental healthcare personnel are more likely to come into contact with bloodborne diseases, including HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C, in their daily duties. In line with the findings of our assessment, 309 of 320 participants (96.6%) concurred that needle-stick and sharp injuries (NSSI) could spread Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and HIV (Pavithran et al., 2015) . This result parallels studies by (Guruprasad, Chauhan, & Knowledge, 2011; Kasat et al., 2014; Saini, 2011) that reported similar findings. The findings of our investigation underline the extensive knowledge among dental practitioners regarding diseases and infections that may emerge from NSSI. Proper safety rules and safeguards are critical for reducing the hazards that these healthcare personnel confront while performing their crucial work.

Dentists undertake several treatments that have the potential to result in NSSIs. Because of the combined effect of these operations, their risk of NSSI is quite significant. The syringe has been found in many studies to be the leading cause of NSSI episodes among dentists. Notably, needle recapping becomes a regular activity; nonetheless, this behaviour is motivated by removing potentially hazardous and sharp items from the surrounding area (Amlak, Tesfa, Tesfamichael, & B, 2023; Bekele, Gebremariam, Kaso, & Ahmed, 2015; Mohamud et al., 2023). Remarkably, more than 20% of survey participants admitted to recapping needles to enhance safety procedures and stop NSSI incidents. The results of the study indicate that inappropriate disposal of sharps and handling of needles while providing patient care has grown in importance as factors that contribute to NSSI incidents. These findings are consistent with other studies that found that recapping and disposing of sharps properly are two crucial factors in NSSI incidences (Almoliky, Elzilal, & Alzahrani, 2024; Amlak et al., 2023; Bekele et al., 2015).

The primary strategy for minimizing bloodborne infections in dental settings is avoiding occupational contact with blood. The CDC emphasized the need for safer tools, such as sharps disposal containers, rubber dams, and self-sheathing anaesthetic needles (Cleveland, Foster, & Barker, 2012). The fundamental strategy for lowering the danger of exposure to bloodborne pathogens after skin penetration by needles or sharp objects is to implement certain safety precautions. Implementing strategies like recapping with one hand, wearing gloves before handling needles, recapping before discarding, and wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) during emergency procedures allows NSSI to avoid (Glarum, Birou, & Cetaruk, 2010). Our study found that 72.8% of participants preferred different preventative measures to counter NSSI; 11.6% specifically mentioned the one-hand recapping technique or the needle scooping approach, while 7% mentioned utilizing personal protective equipment.

When asked how they would want to respond primarily to self-harm events, a significant portion of individuals (39.7%) said they would rather maintain composure and coolness than panic (3.8%) or experience tension (0.3%). The second most frequent reaction from the participants was the fear of becoming sick (33.4%). Twenty-eight per cent of respondents initially chose numerous choices to describe their attitude toward self-harm practices. This is a significant number. The vast majority (304 out of 320) stressed the significance of acting quickly to intervene in any case of self-harm. Almost all participants (99.1%) agreed that putting the proper safety precautions in place might help avoid self-harming behaviours.

The research raises issues regarding underreporting when discussing the difficulty of reporting needle sticks and sharp injuries (NSSI) in dentistry settings. We explicitly asked participants if they thought reporting NSSI instances was essential to learn more about this problem. The findings showed a broad consensus, with an astounding 97.8% of respondents highlighting the importance of reporting NSSI incidences. Nevertheless, even though reporting's significance was widely acknowledged, a sizable minority (77.2%) gave different explanations for not reporting NSSI events. These included a lack of knowledge about related hazards, misunderstandings about how infections spread, and time limits brought on by hectic schedules. While participants understood the importance of reporting NSSIs, many encountered problems, including time constraints, misconceptions, and a lack of awareness of the hazards involved. These results provide insight into the complex factors of NSSI reporting in the dental profession.

There are several considerations for deciding not to report NSSI incidents. Some people believe that NSSI is not severe enough to be worth reporting. Because they may fear being stigmatized, students may be reluctant to report events to staff. NSSI events have occasionally gone unnoticed (Aldakhil, Yenugadhati, Al-Seraihi, Al-Zoughool, & M, 2019). Further investigation has revealed additional contributing factors, including the prioritization of reporting by busy clinical schedules, ignorance of reporting protocols, anxiety regarding patient reactions, worries about the repercussions, convictions about low infection risk, and prompt use of antiseptic measures (Abry et al., 2022) . A complicated web of problems interact to cause underreporting of NSSI incidents. These concerns include patient health, societal stigmatization beliefs, erroneous beliefs about the seriousness of injuries, communication difficulties, and situational factors.

Ninety-six per cent of participants showed an elevated comprehension of the significance of washing wounded areas with soap and water. Only 50% of patients followed the advised method of gently applying pressure to induce bleeding, which is very low. Vigorously irrigating puncture wounds for several minutes is recommended, as well as using sterile water, sterile saline solution, or tap water to minimize the microbial load and dilute bacteria below contagious thresholds. Amazingly, 303 out of 320 participants (94.7%) concurred that sucking the injured region should be avoided. This indicates a thorough understanding of suitable injury treatment techniques and aligns with existing standards for addressing NSSI events (Madhavan, Asokan, Vasudevan, Maniyappan, & Veena, 2019).

The vast majority of participants (84.1%) knew what HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) was. To prevent viral DNA integration and decrease viral multiplication, starting antiviral treatment as soon as possible is crucial—ideally within an hour of exposure, according to CDC guidelines. There is substantial evidence to support the effectiveness of a four-week triple combination medication for HIV prophylaxis, which usually consists of zidovudine, lamivudine, and indinavir (Snyder, D'Argenio, Weislow, Bilello, & Drusano, 2000).

Participants' answers about what they did in the case of an NSSI differed. About one-third said they would contact a doctor or general practitioner (31.9%) while seeing an immunologist (20.6%) was the second most popular choice. A few thoughts about contacting a pathologist (15.3%) or nursing personnel (17.5%). Notably, 41 out of 320 respondents acknowledged not knowing who to contact in this circumstance, indicating a possible lack of awareness on what to do after an NSSI (Sardesai, Gaurkar, Sardesai, & Sardesai, 2018; Wang, Fennie, He, Burgess, & Williams, 2003).

A large percentage of participants (80.3%) think that the Hepatitis B vaccination offers sufficient defence against illnesses brought on by needle-stick and sharp injuries (NSSI). Several studies have shown that dental professionals who receive the Hepatitis B vaccination become quite resistant to infection because they have developed a significant antibody to the virus (Geus, De, & Kintopp, 2021; Ocan et al., 2022). On the other hand, depending on the source person's hepatitis B antigen (HBeAg) status, individuals who choose not to receive the vaccination run a significant risk, which can range from 6% to 30%, when exposed to HBV-infected blood by a single needle-stick or cut. 319 out of 320 respondents strongly agreed that Hepatitis B vaccination is essential. This consensus highlights how necessary and successful Hepatitis B immunization is seen to be in reducing the risk of infection in the wake of NSSI events. It is estimated that 1.8% of cases of Hepatitis C infection are transmitted. HCV prevalence among dental staff varies from 0% to 6.2%. Quick first aid care is essential in the lack of prophylactic measures like medications or immunoglobulins (Ghezeldasht et al., 2017; Westermann, Peters, Lisiak, Lamberti, & Nienhaus, 2015). Surprisingly, 79.4% of participants identified the absence of a vaccine approach for Hepatitis C prevention accurately, underlining the present lack of a successful Hepatitis C vaccination.

The participants identified several resources for information about preventing needle stick and sharp injury (NSSI), such as Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, curricular materials, training programs, and current journal articles. Approximately 71.3% of participants gathered information from many sources, suggesting a thorough approach to data collection. This emphasizes the value of instruction and training to create a comprehensive awareness of general safety measures for handling body fluids. To address NSSI incident prevention successfully, it becomes imperative to emphasize proper training.

Conclusion

In conclusion, NSSIs provide severe occupational dangers in the medical field, especially dentistry, that may influence patients' short- and long-term health. Despite receiving more attention, dentists must comprehend NSSIs. Research indicates a high frequency, which emphasizes the necessity of continuous measures to avoid. NSSIs are caused by several variables, such as the processes followed and safety measures taken. Because of the nature of their employment, dental staff are more vulnerable. Persistent underreporting indicates the need for more study and intervention. Effective NSSI prevention relies heavily on education. Our study fills a significant knowledge vacuum and directs focused initiatives to increase the safety of healthcare workers.

Author contributions

OS., JA., AMP and MIK. conceptualize and design the study; OS., ST., and JA. did data collection; OS., ST., RNM., SB and MIK.. wrote the manuscript; RNM., SB., AML and STK did analysis; JA., AML, STK., AMP and MIK critically reviewed and edited the manuscript; AMP and MIK supervised; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The work has been carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). No personally identifiable data were collected, and responses were anonymous from the point of entry. The approval of the research ethics committee was obtained from the College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Indore, India, with the Ethics approval code (CDSH/738/2023). As the questionnaire was anonymous, informed consent was not applicable. The survey was anonymous and voluntary.